Musicology

This section features current published research on Latin American folk music, as well as essays on aspects and influences of European classical music. With regard to organology and the construction process of musical instruments, this page contains visits to luthiers and instrument makers, workshops attended and short performance demonstrations.

Every year I take the opportunity to attend the annual Spoleto Festival USA in South Carolina to see some of the latest projects in contemporary visual and performing arts. For this year, I witnessed an interview from the Jazz Talks series with jazz critic Larry Blumenfeld and Afro-Cuban jazz drummer, composer, dancer, and Lucumi spiritual leader Pedrito Martinez. As a native from Havana, Cuba, Martinez garnered global recognition after winning the Thelonious Monk Institute of Jazz International Afro-Latin Hand Drum Competition in 2000 and has since gone on to perform with several jazz ensembles and to collaborate with various popular musical artists across genres over the course of his long career. In discussing his latest musical project entitled Echoes of Africa, I noticed many parallels to the ethnographic research that I have conducted about syncretic religion and the Afro-Latin diaspora. I became especially intrigued by how, as both an artist and Lucumi priest, Pedrito Martinez attempts to incorporates ancestral reverence and spiritual healing into his works. I also liked how he openly acknowledges the African presence throughout history: not just in Cuba, but throughout Latin America and the rest of the world.

The Impact of Military Drumming in War

Throughout my travels this unusual summer, I have had the opportunity to reflect on how past generations applied music in times of conflict. Such is the case with the drummer boys of the Civil War in the early 1860s. According to Carolyn Reeder and Marcie Schwarz in their respective research, drummer boys often enlisted in this position at the young age of twelve, marching and performing together with Union and Confederate troops in battle. The drummer boys in the Civil War also needed to remember to play specific rhythmic, coded messages on the battlefield: when to attack, when to retreat, and so on. Concerning combat, multiple historical records and writings from the period note that young teenagers frequently enlisted for the experience: many of whom lied about their age so that they could join and fight. Several archives and museums across the United States feature artifacts of Civil War musical instruments and scores performed by drum corps and band during the era. One of the most important period compilations of notated drumming from the Civil War derives from the United States Drum and Fife Instructor (1862) by Elias Howe. This book devotes time to developing drumming techniques and mastering specific drumming commands.

Reflections on Preserved Traditions for Those Who Died Serving Their Country

Music has formed a vital component for remembering and respecting those who have fallen in battle. Memorial Day initially began as “Decoration Day” in the late 1860s, named for the custom of honoring deceased U.S. soldiers by placing flags and other appropriate decorations near their tombstones. As is common during Memorial Day, “Taps” brass music is performed during this somber U.S. holiday. In terms of classical music, composer Charles Ives sought to recapture this attitude of as part of his Holiday Symphony with the movement entitled “Decoration Day.”

It also deserves mention that audio recordings from the past have helped to archive and preserve Memorial Day and provide commentary on the plethora of conflicts that the United States Armed Forces have endured. The Library of Congress website features many accessible audio recordings of music and speech from the early twentieth century, beginning around World War I. The website contains records dedicated to speeches or poems about Decoration Day, the war effort at certain points in time, the effects of conflicts on the United States, and reflections on how the country recuperated from war. The digital restorations of these recordings at the Library of Congress website are in surprisingly good condition, given that many of them are over a century old. These recordings have been cataloged in multiple archives and can be accessed under certain conditions. They are presented mainly for educational purposes under “Fair Use.” Despite the age of the older recorded materials, some are still within copyright. This is the case for songs like “Over There” by George Michael Mason, even though this song dates from 1917. In many instances, the Library of Congress strongly urges people to carefully follow copyright rules by contacting the copyright owner for obtaining permission(s) to use these materials outside of academia and research.

It also deserves mention that audio recordings from the past have helped to archive and preserve Memorial Day and provide commentary on the plethora of conflicts that the United States Armed Forces have endured. The Library of Congress website features many accessible audio recordings of music and speech from the early twentieth century, beginning around World War I. The website contains records dedicated to speeches or poems about Decoration Day, the war effort at certain points in time, the effects of conflicts on the United States, and reflections on how the country recuperated from war. The digital restorations of these recordings at the Library of Congress website are in surprisingly good condition, given that many of them are over a century old. These recordings have been cataloged in multiple archives and can be accessed under certain conditions. They are presented mainly for educational purposes under “Fair Use.” Despite the age of the older recorded materials, some are still within copyright. This is the case for songs like “Over There” by George Michael Mason, even though this song dates from 1917. In many instances, the Library of Congress strongly urges people to carefully follow copyright rules by contacting the copyright owner for obtaining permission(s) to use these materials outside of academia and research.

Celebrating Jazz in Isolation

On International Jazz Day, I would also like to take a moment to briefly talk about the impact of jazz on the Hispanophone Caribbean through Puerto Rico. In previous posts and research, I examined the Puerto Rican cuatro string instrument as the symbol of folkloric music culture on the island. This instrument has also been used extensively by cuatristas like Pedro Guzman through the folk and jazz combination known as jibaro jazz. Scholarship on that topic is surprising scant, despite its musical impact on the island through cuatro jazz festivals (The latest research that I encountered in quick investigations stemmed from 1989 and 2015). It also deserves mention that I incorporated elements of the jibaro jazz genre within a contemporary classical setting in Estampas de La Isla del Encanto (2015-16). I realize that incorporating jazz elements in classical music has been done before, like the concert pieces by George Gershwin. Unlike those attempts, which have the parts written out, I included improvisatory sections written in my score as “slash-notation.” I wanted to give the performers enough freedom to play their improvised “take-offs” within the confines of the given key and measure numbers. I also made sure that other performers participated in improvisation so that the musical focus did not rely solely on one instrumentalist. Here is a performance from members of the Chicago Cuatro Orchestra:

Today would have marked public celebrations sponsored by UNESCO on International Jazz Day. Because of the effects of COVID-19, the organization has has had to restructure events. Festivities will take place onlune via live streaming, with musicians from around the world performing in the comfort and safety of their homes. More details about the event can be found at the International Jazz Day website and YouTube channel..

Music and its Environmental Connections

This Earth Day, I wanted to concentrate on an ecological problem that has been affecting the musical realm for centuries. My previous research on musical instrument construction—specifically, of percussion and plucked chordophones—indicated that instrument makers use specific types of wood from the natural environment. The quality of the wood and climate (depending on geographical location) affect the overall tone quality of the instrument. The same could be said for bowed chordophones and keyboard instruments, like violins and pianos. One must also include the archaic European and Colonial American musical instruments often combined natural materials with gut strings made out of animal parts, as well as bones and animal skins for indigenous and African instruments. Here are some examples of early construction stages for percussion and string instruments used in Latin America and the Hispanophone Caribbean:

In terms of musical instruments in contemporary times, the obstacles that musical instrument and equipment makers encounter today does not simply lie in the types of resources that they use. Those who specialize in making musical devices can still be masters of their craft and maintain traditions while still being environmentally conscious. The problem lies in overusing natural materials until they become scarce or extinct. One quick solution that manufacturers have had to adapt to keep up with high demand, specifically with guitars, is to switch to different types of wood. This approach, of course, just prolongs the looming threat of deforestation. They have also had to consider the environmental impact of using materials that are not biodegradable, like plastic and metal. Conducting a quick online search reveals several companies who create eco-friendly products, like D’Addario from New York City. That company also applies a string recycling rewards program to help encourage environmental sustainability. However, if using a tree is necessary, then one must make sure that another tree is planted for future generations.

What Would Mardi Gras Be Without Music?

For centuries, music has formed a vital component of Mardi Gras celebrations in New Orleans. It serves to complement the festive atmosphere of colorful pageantry and parade floats before the solemn Lenten observance. The musical components of Mardi Gras additionally allude to the diversity of cultures in the city throughout its history. Although jazz music does function as part of the musical celebrations, it is not the only genre performed. Mardi Gras music also stresses the inclusion of other styles, like second line music, rhythm and blues and zydeco. “Second line” refers to the group that follows the “main line” of a parade: usually, as a brass band ensemble and other viewers who walk along the parade path. Zydeco, a French Creole music developed in the 1950s by accordionist and singer Clifton Chenier (1925-1987), functions as an offshoot of the older “French Music” genre (which combined Cajun and Creole musical elements). As some have pointed out, Zydeco should not be confused as being synonymous with Cajun music, which—in its contemporary format—applies aspects of country music.

Music for the New Generation

Earlier on this page, I briefly talked about the artistic and African American social contributions of the Johnson brothers in the early twentieth century. I will concentrate, now, on two other musically inclined brothers from more contemporary times. The Sons of Mystero (pronounced “Maestro”) have devoted their artistic careers to performing as a violin duo for mass audiences everywhere. Umoja and Malcom Macneish both received their musical training in areas of Florida (Ft. Lauderdale and Miami), They primarily utilize electric violins in their performances and fuse elements of classical and popular music from multiple genres: from R&B, to rap, hip-hop and modern pop hits. This approach has helped to increase their fan base and encourage the younger generation of African Americans to pursue interest in the violin and music studies. As I observed in one of their performances, the Sons of Mystro included a disc jockey who played remixes of popular music (and some original works) in coordination with the violin duet performances. It also featured moments displaying the technical virtuosity of the electric violin, like a riveting solo arrangement of the 1963 Sam Cooke song, “A Change Is Gonna’ Come.”

The Power of Family and Collaboration

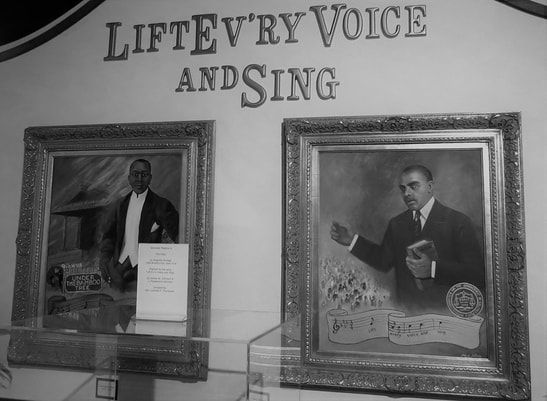

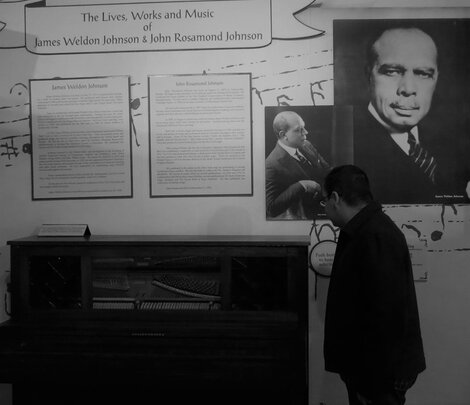

As I continue the discussion about the achievements of the Johnson brothers, I wanted to draw attention to the similarities in their career paths. Both worked to a certain degree in the arts and politics. James established himself as a poet, composer and African American civil rights advocate: serving as a member of the NAACP and global diplomat for areas of Latin America. Although he is often remembered for “Lift Every Voice and Sing” and his collections of poems entitled God’s Trombones (1927), James also collaborated with his brother and Robert Cole to produce Vaudeville plays and musical productions in New York City beginning in the 1900s These productions were unique in that they featured all-Black cast members, like The Shoo-Fly Regiment from 1906. Some productions additionally paid respect to Native Americans, such as The Red Moon from 1908 to 1910. In addition to his work as a composer and Civil Rights activist, John devoted his life to acting. He often starred in leading roles in productions for Porgy and Bess (1935) and Cabin in the Sky (1940), among others. He also contributed to music education by founding the New York Music School Settlement for Colored People (1918) in Harlem.

Music to Persevere and Empower

“Lift Ev'ry Voice and Sing” has served as a poignant song for the African American communities for the past one-hundred-twenty years. Originally composed in 1900, the song functioned as a choral piece for schoolchildren in Jacksonville, Florida to commemorate the birth of Abraham Lincoln. The lyrics provide social commentary on the past and present struggles that African Americans have faced throughout the centuries (from slavery, to racial discrimination imposed by the Jim Crow laws), as well as offering hope for the future generations. Over time, “Lift Ev'ry Voice and Sing” has transformed in context as a song promoting activism and civil rights. Since 1919, this song has been used as the official anthem for the NAACP and is often regarded as the African American national anthem. It also deserves mention that this song is sung by members of the Gullah Geechee communities in the coastal areas from North Florida to the Carolinas to preserve the culture and instill peace. In the next post, I will devote time to discussing the composer and lyricist involved in writing the song.

In the Holiday Spirit

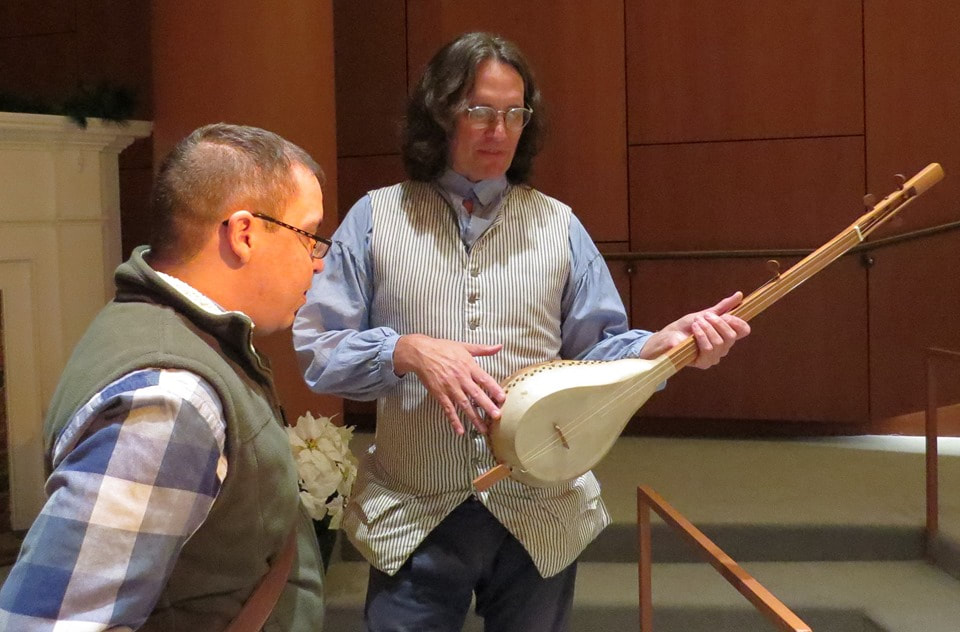

Here is a selection of chordophone and woodwind Instruments from the American Colonial Era performed by the Waterman Family and other musicians in Williamsburg and Jamestown, Virginia. These serve as examples of the types of musical instruments that common people would have used for entertainment in the 1700s around the Christmas season. It helps to think about this point within the context of the customs of the time. Remember that Christmas back then did not rely heavily on commercialism as it did in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. One must also consider that the Puritans banned Christmas in the new England colonies in the 1600s on the basis of Biblical inaccuracy.

Aside from the recorder and guitar shown below, which consisted of an elongated "figure-eight" body and ten strings (in five pairs), the gourd banjo and mountain dulcimer especially caught my attention. The gourd banjo derives from The Gambia, Africa and has figured prominently in the West Indies and Colonial American music culture. Concerning the connection to the colonies, the instrument arrived via the Transatlantic Slave Trade and functioned as an instrument used to accompany dancing and other forms of entertainment. Thomas Jefferson had documented the gourd banjo in the early 1780s, in which he referred to the instrument as the banjar. Although the gourd banjo (and other variants of the banjo) originally became associated with part of African and African American music culture, the instrument gradually transformed as an appropriated chordophone linked with Appalachian folk music.

Another instrument closely associated with Appalachian folk music culture is the mountain dulcimer. The instrument varies in shape: either rectangular, or with a long "figure-eight" body. The mountain dulcimer features four strings and can be hit with sticks or mallets to produce sound. This instrument should not be confused with the hammered dulcimer, which features a trapezoidal shape and more strings, which are usually plucked. The mountain dulcimer that I observed appeared rather unusual in terms of its performative aspects. It was tuned to the key of G and functioned as a percussive instrument, with an emphasis on open fifths every time the sticks hit the strings.

Aside from the recorder and guitar shown below, which consisted of an elongated "figure-eight" body and ten strings (in five pairs), the gourd banjo and mountain dulcimer especially caught my attention. The gourd banjo derives from The Gambia, Africa and has figured prominently in the West Indies and Colonial American music culture. Concerning the connection to the colonies, the instrument arrived via the Transatlantic Slave Trade and functioned as an instrument used to accompany dancing and other forms of entertainment. Thomas Jefferson had documented the gourd banjo in the early 1780s, in which he referred to the instrument as the banjar. Although the gourd banjo (and other variants of the banjo) originally became associated with part of African and African American music culture, the instrument gradually transformed as an appropriated chordophone linked with Appalachian folk music.

Another instrument closely associated with Appalachian folk music culture is the mountain dulcimer. The instrument varies in shape: either rectangular, or with a long "figure-eight" body. The mountain dulcimer features four strings and can be hit with sticks or mallets to produce sound. This instrument should not be confused with the hammered dulcimer, which features a trapezoidal shape and more strings, which are usually plucked. The mountain dulcimer that I observed appeared rather unusual in terms of its performative aspects. It was tuned to the key of G and functioned as a percussive instrument, with an emphasis on open fifths every time the sticks hit the strings.

The Sound of the Highlands

The Highland bagpipe serves as the national instrument of Scotland. The history behind its musical organology, however, indicates multiple variants of bagpipes that extend to other areas of the United Kingdom (like Ireland). These types of instruments have also existed throughout areas of Africa, Europe, Asia.The Highland bagpipe, in its modern format, features a blowstick with three drone reeds at the top the instrument: one long bass drone and two smaller tenor drones. I say "modern" because some bagpipe ensembles mention that the total number of drone reeds changed over the centuries from around the 1300s, to the 1700s. The chanter reed at the bottom consists of finger holes for shaping different notes when blowing air through the blowstick. The construction of these reeds usually contains a combination of cane wood and plastic and connect to a bag made from sheep or cow bladder, which helps to transfer the air from the blowstick when the bag is filled and squeezed. The photos below show Ben. from a bagpipe band from Atlanta, and I at a bagpipe competition in Charleston, South Carolina.

bThe musical range for the Highland Bagpipe consists of nine notes (one octave with a flat seventh scale tone plus one extra note after the octave). This instrument is often tuned to the key of B-Flat, although slight changes in climate will alter the acoustics of the pitches. Highland bagpipes can be used for military and secular recreational purposes. In terms of its application in military music, some researchers indicate that this function served as a form of British appropriation of the instrument. This type of performance often requires synchronization with drummers and other pipers by playing and (in certain cases) marching in unison. Below is an example of the adjudication process for bagpipe bands from the southeastern United States. Considering its use in this country, the Highland Bagpipes serve to promote and preserve the legacy of Scottish and Scotch-Irish identities through annual festivals.

Blending Tradition with Modernity

The bouzouki is a plucked string musical instrument of Turkish and Greek origins belonging to the lute family. Since the early twentieth century, it has been used in the performance of Greek rebetiko music. Bouzouki construction consists of a tear-shaped body and long, thin neck. Concerning its total number of strings, the bouzouki often features either six or eight strings. Like the Puerto Rican cuatro, which I had discussed in previous posts on this website, the strings of a bouzouki are arranged by courses, or pairs. Also, like the cuatro, the bouzouki often utilizes tablature to denote the corresponding string number and fret position instead of regular notation. Tuning a bouzouki depends on the type of instrument and the total number of strings. I say this because the bouzouki also exists in Ireland, albeit with a slightly different shape (The Irish bouzouki contains a flatter back in the construction of the body of the instrument, unlike the round back of the Greek bouzouki.). Because of this difference, details about the bouzouki try to provide clarifications between the Greek and Irish versions. Standard tunings for the Greek bouzouki consist of the following:

6-string Greek bouzouki: D3-A3-D4

For 8-string Greek bouzouki: C3-F3-A3-D4

In these contemporary times, the bouzouki exists as either an acoustic or electric instrument: “electric” in the sense that the instrument can be plugged into an amplifier and adjusted for sonic balance. The musician Leonidas Zafiris (shown below) has been performing on the bouzouki for the past thirty years. The electric bouzouki that he showed me consisted of eight strings (four courses) and used a hollow body, which I found intriguing. Perhaps, it helps to impact the overall resonance, or to stress the almost futuristic design of the instrument.

6-string Greek bouzouki: D3-A3-D4

For 8-string Greek bouzouki: C3-F3-A3-D4

In these contemporary times, the bouzouki exists as either an acoustic or electric instrument: “electric” in the sense that the instrument can be plugged into an amplifier and adjusted for sonic balance. The musician Leonidas Zafiris (shown below) has been performing on the bouzouki for the past thirty years. The electric bouzouki that he showed me consisted of eight strings (four courses) and used a hollow body, which I found intriguing. Perhaps, it helps to impact the overall resonance, or to stress the almost futuristic design of the instrument.

On Popular Music and Appropriation

It has often been said that, to understand certain chapters in history, one must try to understand who is telling the story and determine its overall tone. As many are probably aware by now, 2019 commemorates a solemn event in United States history by marking the four-hundredth anniversary of African slavery in the country in 1619. Most scholars have accepted this year as the initial date, despite some disagreement on the focus of this history. It especially deserves mention that, in discussing this topic, one must also consider the sociocultural impact of music and the problem of cultural theft via appropriation. Within this context, people must determine who is performing the music and from what artistic background.

Some may have noticed an article from “The 1619 Project” that I shared to my Facebook composer page the other day. In that article, the critic Wesley Morris primarily discusses how white musical artists from the U.S. and have frequently have taken from African American musical genres and vocal styles, often reclaiming the music as their own in the process. While Morris does express frustration over this tendency in popular music, he does so for good reason. What he reveals is a painful chronology spanning from the 1830s with minstrel shows, to today with the release of songs like “Old Town Road” by Lil’ Nas X: a song which combines elements of country and rap… that country music radio stations refused to play. Morris demonstrates to readers that appropriation of African American music has occurred for centuries and that, as of the 2010s, the United States is still grappling with this problem in the entertainment industry.

Some may have noticed an article from “The 1619 Project” that I shared to my Facebook composer page the other day. In that article, the critic Wesley Morris primarily discusses how white musical artists from the U.S. and have frequently have taken from African American musical genres and vocal styles, often reclaiming the music as their own in the process. While Morris does express frustration over this tendency in popular music, he does so for good reason. What he reveals is a painful chronology spanning from the 1830s with minstrel shows, to today with the release of songs like “Old Town Road” by Lil’ Nas X: a song which combines elements of country and rap… that country music radio stations refused to play. Morris demonstrates to readers that appropriation of African American music has occurred for centuries and that, as of the 2010s, the United States is still grappling with this problem in the entertainment industry.

Folk Music from Island to Island

Shortly before I left for Puerto Rico, I met several Hawaiian musicians at an annual Polynesian culture convention in Orlando, Florida. Many of these performers, who played ukuleles and guitars, were also instruments makers. Their method for constructing these string instruments adheres to almost the same process that Puerto Rican string instrument makers follow, in that both cultures rely on wood native to the respective islands. In this respect, Hawaii and Puerto Rico share another cultural connection: that of transnationalism through migration. The destruction caused by Hurricane San Ciriaco in 1899 caused many Puerto Ricans to migrate to Hawaii the following year in 1900 and adapt to new surroundings. Part of this cultural adjustment resulted in the creation of fused musical styles from Polynesia and the Hispanophone Caribbean: music like “Kachi Kachi,” which combines Puerto Rican and Hawaiian folk music and instruments. As the musicians at the convention assured me, this style of folk music is still performed in Hawaii to this day. Examples of Puerto Rican folk music from Hawaii, released under the Smithsonian Folkways Recordings label in 1989, can be found on Spotify via the following link: https://open.spotify.com/album/4T83Y5zwmf8Nm3KpSTg7oA

Preserving Musical Traditions in Modern Times

Many instrument makers in the twenty-first century are inclined to promote their musical products by showcasing their artistry and challenging visual perceptions. In this way, they manage to fuse the traditional with the contemporary as a means of preserving their craft. Puerto Rico is not exempt from such an approach. I recently met an instrument maker on the island who specialized in constructing acoustic and electroacoustic plucked string instruments: most notably, the guitar and cuatro (a ten-string instrument with five pairs of doubled strings). In keeping with the instrument making tradition in Puerto Rico, he often creates his instruments from wood native to the island, such as the blue mahogany that he applies as the basis for building cuatros and guitars. This instrument maker also deviates from convention by constructing hollow-bodied electric versions of Puerto Rican instruments (ones that intentionally look like a skeletal frame) or experimenting with different shapes. In my conversation with him, he showed me previous projects where he built instruments in the shapes of musical clefs.

African Rhythms of the Island

Loiza, a coastal municipality about forty-five minutes away from the capital of Puerto Rico, represents an area of the island predominantly populated by Afro-Puerto Ricans. In terms of musical output, the area is best known for the bomba: a percussive communal song and dance that uses barrel drums and a vocal “Call and Response” format. Like many areas of Puerto Rico, Loiza features festivals that combine religious Christian traditions from Europe with the influence of Santeria from the African heritage on the island.

In the Department of Arts and Culture, I found many Afro-Puerto Rican and Taino artifacts—including musical instruments. This center strives to preserve the local customs and archaeological discoveries, despite being greatly affected by Hurricane Maria in 2017. Ten minutes outside the town, I also visited the Batey de los Hermanos Ayala (The Ayala Bothers Settlement). The word "batey" refers to a space outside the house for dance and community events. It usually consisted in the past of a small barren space either in the back or front of the house. The Ayala Brothers are a large family of folk dancers and musicians of bomba. The small, colorful house features objects associated with their traditions, which have been passed down from their previous generations.

It is worth mentioning that, in late summer, Loiza celebrates the Festival of St. James the Apostle. The event is intended to honor St. James, the patron saint of the Christian (Catholic) Spanish military and his involvement in defeating the Moors in the Crusades. He is often portrayed as riding on horseback into battle. Symbolism and artistic elements alluding to Santeria manifest themselves through objects like the vejigante mask, constructed from coconuts.

In the Department of Arts and Culture, I found many Afro-Puerto Rican and Taino artifacts—including musical instruments. This center strives to preserve the local customs and archaeological discoveries, despite being greatly affected by Hurricane Maria in 2017. Ten minutes outside the town, I also visited the Batey de los Hermanos Ayala (The Ayala Bothers Settlement). The word "batey" refers to a space outside the house for dance and community events. It usually consisted in the past of a small barren space either in the back or front of the house. The Ayala Brothers are a large family of folk dancers and musicians of bomba. The small, colorful house features objects associated with their traditions, which have been passed down from their previous generations.

It is worth mentioning that, in late summer, Loiza celebrates the Festival of St. James the Apostle. The event is intended to honor St. James, the patron saint of the Christian (Catholic) Spanish military and his involvement in defeating the Moors in the Crusades. He is often portrayed as riding on horseback into battle. Symbolism and artistic elements alluding to Santeria manifest themselves through objects like the vejigante mask, constructed from coconuts.

Making Music from Everyday Objects

Re-purposing found objects and determining their aspects of musicality demonstrates historical and cultural links with the arts and music. The images and video clip shown in this post derive from common gas cylinders converted into hang drums. Each gas cylinder consisted of resonant grooves on the surface, arranged in a circle and applying a heptatonic (seven-note) scale. These instruments would produce different timbres depending on where people hit a given container with a mallet in proximity to the grooves. This action would also include hitting the center of the container, which produced an audible tone in accordance with the hang drum instrument configuration. It also deserves mention that the various visual designs by different artists reflected the ethereal nature of the installation.

In relation to Puerto Rican music culture, the installation addresses connections to the Taino, African and European lineages in that objects from the natural environment can serve as musical instrument regardless of shape or form. On another level, the interactive musical and visual installation also served as subtle commentary concerning ecology and spirituality. In other words, it confronted the issue of establishing environmental unity by creating new materials from objects usually considered in contemporary society as products that promote pollution.

In relation to Puerto Rican music culture, the installation addresses connections to the Taino, African and European lineages in that objects from the natural environment can serve as musical instrument regardless of shape or form. On another level, the interactive musical and visual installation also served as subtle commentary concerning ecology and spirituality. In other words, it confronted the issue of establishing environmental unity by creating new materials from objects usually considered in contemporary society as products that promote pollution.

Video excerpt taken July 26th, 2019 in San Juan, Puerto Rico

Title: Esculturas Sonoras

Credit: (Visual Arts and Music) by Jaime Bofill Calero and Enrique Cárdenas

Title: Esculturas Sonoras

Credit: (Visual Arts and Music) by Jaime Bofill Calero and Enrique Cárdenas

Artistic Social Expression in the Hispanophone Caribbean

Readers and viewers might recall that I had been travelling abroad for over two weeks. More specifically, I visited the island of Puerto Rico both for recreational and research purposes. Throughout my time there, I also inadvertently witnessed moments of civil unrest and several drastic shifts in governing power. Puerto Rico is currently being governed by the former Secretary of Justice as a result of procedural difficulties due to a legal misinterpretation of the Puerto Rican Constitution of 1952. Some may wonder how this last point relates to music. The answer lies in how history has demonstrated that the arts can serve as vehicles for candidly addressing social problems and promoting peaceful protest, regardless of geographic location.

While staying in the capital city of San Juan in the historic district (Old San Juan), I met an upcoming poet and spoken word artist who went by the pseudonym of “Crazy Tony.” His latest collaborative album with electronic artist DJ Pangui offers more than a combination of poetry and a musical backdrop. The seven tracks on the disc address myriad topics concerning Puerto Rican history, culture and society and depict various changes in mood. At times, Tony and DJ Pangui allude to the African and European heritage in Puerto Rico by evoking or sampling aspects of the bomba and musica jibara, or folk music of the mountain men of the island. In other instances, they present graphically intense thematic material by talking about social problems in contemporary Puerto Rico. The poems on the album concerning aspects of the drug epidemic, gang violence and poverty often depict a bleak atmosphere, followed by moments of hope for a better future for the people of the island.

While staying in the capital city of San Juan in the historic district (Old San Juan), I met an upcoming poet and spoken word artist who went by the pseudonym of “Crazy Tony.” His latest collaborative album with electronic artist DJ Pangui offers more than a combination of poetry and a musical backdrop. The seven tracks on the disc address myriad topics concerning Puerto Rican history, culture and society and depict various changes in mood. At times, Tony and DJ Pangui allude to the African and European heritage in Puerto Rico by evoking or sampling aspects of the bomba and musica jibara, or folk music of the mountain men of the island. In other instances, they present graphically intense thematic material by talking about social problems in contemporary Puerto Rico. The poems on the album concerning aspects of the drug epidemic, gang violence and poverty often depict a bleak atmosphere, followed by moments of hope for a better future for the people of the island.

Cultural Connections Between American Jazz and Afro-Cuban Musical Elements

The pianist and composer David Virelles and percussionist Ramon Diaz (shown on the right) were part of a series of discussions on jazz music. Virelles, who grew up in a family of musicians in Santiago de Cuba, studied classical music at the Conservatory in his hometown. His influence in jazz stem from his fascination with the bebop music of Bud Powell and Thelonius Monk, as well as many lesser-known but talented musicians from Santiago skilled in Cuban rhythms.. With regard to the Cuban influences in his music, Virellles explained the importance of popular musical styles from his island and how artists like he and those before him combined this music with jazz (or musica creativa).. Concerning his work with Roman Diaz, such as the album Gnosis (2017), I perceive their inclusion of Afro-Cuban elements in avant-garde jazz as more than merely a novelty or exoticism. By applying narrations in Afro-Cuban dialects and drumming patterns reminiscent of ceremonial dance, Virelles and Diaz openly acknowledge Cuba's past within the context of the twenty-first century.

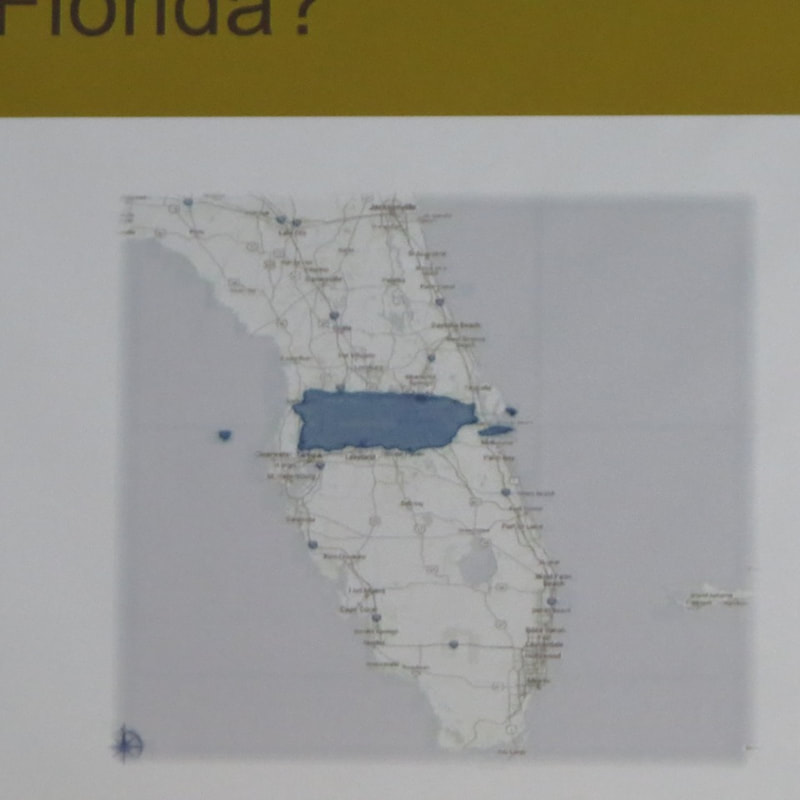

A Summit at UCF

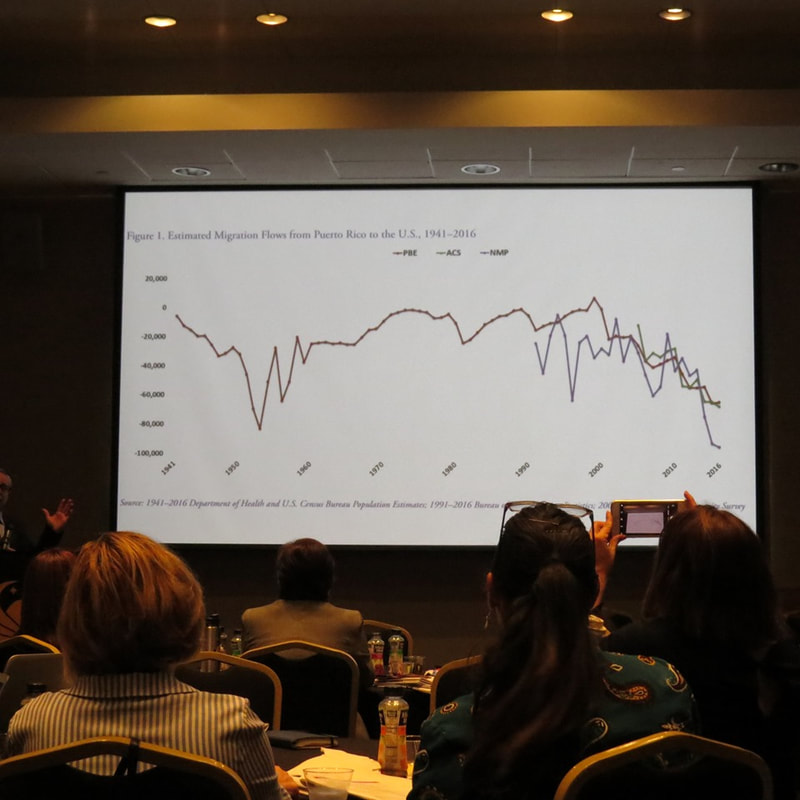

I had the opportunity to attend a series of lectures and debates concerning the migration of Puerto Ricans in Florida. While the discussions mainly focused on the sociocultural and economic effects of this process, my main concern was the preservation of the folkloric musical traditions and cultural memory on the island and the transnational or transcultural effects through performances in the state. This summit was made possible through a partnership between University of Central Florida in Orlando and Centro PR at Hunter College in New York.

Music from (Another) Part of Colonial America

A few weeks ago, I had the chance to visit Historic St. Augustine, Florida and meet a group of re-enactors and drum corp. The drum is considered by many musicologists to be one of the oldest instruments used for military purposes. According to Ricardo Fernandez de la Torre, a specialist on the music of the Spanish military, the origins of the drum as a military instrument probably originated from two different cultures: either from the ancient Romans (who applied the drum as an accompaniment for marches into battle), or from the Saracen troops in the Crusades in the Middle Ages (who used the drum as a tactical tool to intimidate the Europeans).

The drum shown in the photos below represent the atabal, or timbal drum, which Fernandez de la Torre indicates as an instrument that the Spanish Military used in combat from the fifteenth to late nineteenth century: at times, incorporating a lead drummer as part of a Tercio (a group of infantry soldiers active in the Habsburg Dynasty). As can be seen in the photographs, members of the Spanish military also performed on the atabal in areas of colonial North America when in battle, for parades or for military exercises.

The drum shown in the photos below represent the atabal, or timbal drum, which Fernandez de la Torre indicates as an instrument that the Spanish Military used in combat from the fifteenth to late nineteenth century: at times, incorporating a lead drummer as part of a Tercio (a group of infantry soldiers active in the Habsburg Dynasty). As can be seen in the photographs, members of the Spanish military also performed on the atabal in areas of colonial North America when in battle, for parades or for military exercises.

Music as a Communal Force

Throughout this month, in recognition of Black History, I have had the opportunity to attend several celebratory events in Mitchellville, South Carolina: events such as the “National Freedom Day” commemoration honoring the signing of the Thirteenth Amendment of the Constitution into law. While at this event, I met Dr. Johnnie P. Mitchell (who helped to promote “National Freedom Day” as an official holiday in the United States) and cultural interpreters, like Aunt Pearlie Sue. Mitchellville represents a significant historical colony from the 1860s, consisting of freed African slaves of Gullah Geechee (West African) origin.

Located along the coastal areas of Georgia, South Carolina and parts of north Florida in what is known as “The Corridor,” the Gullah Geechee Nation serves as one of the oldest African communities living and thriving in the United States. Gullah Geechee culture consists of combined customs from enslaved West Africans and European conquerors in the US colonial period by using an English dialect. Music and dance form essential components of Gullah Geechee society through choral music (mainly, spirituals) and accompanied percussion through clapping or drumming. In certain cases, the lyrics to some spirituals applied secret code words or phrases that referred to freedom from slavery. Gullah Geechee culture has been preserved for future generations of people through educational programs and musical performances aimed at demonstrating aspects about the Gullah Geechee.

Located along the coastal areas of Georgia, South Carolina and parts of north Florida in what is known as “The Corridor,” the Gullah Geechee Nation serves as one of the oldest African communities living and thriving in the United States. Gullah Geechee culture consists of combined customs from enslaved West Africans and European conquerors in the US colonial period by using an English dialect. Music and dance form essential components of Gullah Geechee society through choral music (mainly, spirituals) and accompanied percussion through clapping or drumming. In certain cases, the lyrics to some spirituals applied secret code words or phrases that referred to freedom from slavery. Gullah Geechee culture has been preserved for future generations of people through educational programs and musical performances aimed at demonstrating aspects about the Gullah Geechee.

The Life of a Musician

The following photographs were taken during a trip to Nashville, TN in November. When exploring the downtown area of the capital city, I noticed many singers/songwriters and bands performing hourly gigs in restaurants and bars on almost every block (top row). In many respects, experiencing this music felt almost like browsing store window displays.

Seeing these aspiring performers downtown, I realized how many of them have probably struggled artistically to make themselves known and boost their career. Performers play in the restaurants and bars in the hopes that record executives will eventually recognize their talents. Those familiar with country music know the tremendous importance that the Ryman Auditorium and Grand Ole Opry (bottom row) hold for new musicians. Musicians who make it to Ryman and the Grand Ole Opry understand that they have succeeded as artists.

Seeing these aspiring performers downtown, I realized how many of them have probably struggled artistically to make themselves known and boost their career. Performers play in the restaurants and bars in the hopes that record executives will eventually recognize their talents. Those familiar with country music know the tremendous importance that the Ryman Auditorium and Grand Ole Opry (bottom row) hold for new musicians. Musicians who make it to Ryman and the Grand Ole Opry understand that they have succeeded as artists.

Re-Thinking Folk Music Cultures

The month of November has been both hectic and rewarding, as I had the pleasure of attending symposia dedicated to uncovering more about American music: specifically, the contemporary ethnographic fieldwork, music-related artistic projects and and the preservation of folk music and instruments (like the so-called "one string on the wall," banjo, fiddle, etc.). These lectures elicited new information that encouraged people to reconsider previous misconceptions about the musical impact of the southern region of the United States and its people. Some of the topics covered included the following:

-The origins of Reconstruction in the United States and its effect on the African Gullah community

-The Gullah connection to jazz music, which went beyond the New Orleans-centric approach to jazz history

- The impact of Latin American and other foreign immigration on southern folk music recordings from the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

- Applying oral history and cultural memory through traditional photography and filming in the twenty-first century as ways for preserving the legacy of rural southern folk music and communities

-The origins of Reconstruction in the United States and its effect on the African Gullah community

-The Gullah connection to jazz music, which went beyond the New Orleans-centric approach to jazz history

- The impact of Latin American and other foreign immigration on southern folk music recordings from the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

- Applying oral history and cultural memory through traditional photography and filming in the twenty-first century as ways for preserving the legacy of rural southern folk music and communities

A Piece of African Music Culture

The following photos were taken during an event promoting African American and Afro-Caribbean cultures: specifically, from Anglophone (British) Caribbean. I met this woman named Mary (far-left), who creates African instruments from gourds. The instrument that she holds in her hands is a shekere: a gourd hand percussion instrument with beads—usually on the outside—made for shaking. This instrument is often performed with both hands.

Music Without Language Barriers

These are instructors and Music students from Martin Luther University in Halle, Germany: representing the Music department of the university's second Faculty of Arts (of which, there are three total). I had the opportunity to meet with Prof. Dr. Hans Joachim Solms, the Head of the Germanist Institute who helped to promote Halle tourism and events, like the Handel Festival. That festival bears significance because the Baroque composer George Frideric Handel was born in Halle and lived there until his late-20s, when he moved to London, England to write his oratorios and other music for the Royal Court.

Taino Mayohuacan Demonstrations (Videos)

Awhile back, I posted several photos about the Taino mayohuacan drum and its construction process. Here are two brief videos demonstrating what the instrument sounds like. The mayohuacan drums shown in these videos were made as part of my chamber piece, Estampas de la Isla del Encanto (2015-16). The designs presented on these drums derive from Taino symbols.

|

|

|

A New Kind of Latin Jazz

I had the opportunity to hear wonderful jazz music inspired by Afro-Cuban culture. The following photos are of Jane Bunnett and her ensemble known as Maqueque (formed in 2013). The name for their ensemble roughly translates into English as " the energy of a little girl." A native of Toronto, Bunnett has participated in musical diplomacy with Cuba, Canada and (sometimes) the United States since the 1980s and 90s. Bunnett and her husband have often traveled to Cuba to learn about the culture, teach jazz to the younger generation of people over there, and (most important) recruit female Cuban musicians to perform with her in Canada and around the world. In so doing, Bunnett has helped these musicians free themselves from the restrictive and often sexist nature of the Cuban conservatories and society, which would mainly promote European classical music over Cuban folk music culture and discourage female musicians from performing professionally in their country.

Another Side of Jazz History: Savannah, GA

This week, I have been attending and observing a new generation of jazz musicians performing and preserving the legacy of what many consider to be an important component of American music. These musicians exhibited their talents in showcasing the musical genres from blues and gospel, to Latin jazz. I found it interesting that most of these musicians live in the city, but they are transplants from other areas. In terms of jazz music history, most scholars tend to concentrate on the major cities that promoted and expanded this music, like New Orleans and others. The coastal city of Savannah, GA also deserves attention because of its impact and long history on jazz since the early twentieth century. It has produced iconic musicians like James Moody and Ben Tucker. Jazz music also had a big impact on acclaimed songwriter and composer Johnny Mercer. As Louis Armstrong once said, “If you have to ask what jazz is, you'll never know.”

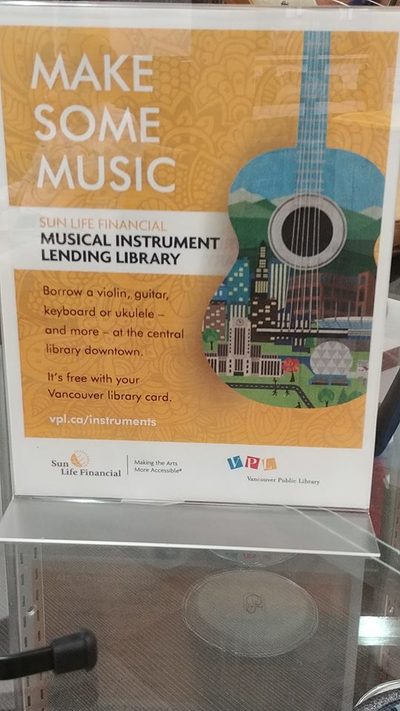

Free Recording Studios?

This is what I encountered while visiting the Vancouver Public Library. These are instrumental and vocal recording studio booths that can be reserved if you have a library card, with sophisticated recording equipment. It is quite rare to see this kind of service to the community. Also, this library features various Western and non-Western musical instruments on loan.

United by Sounds

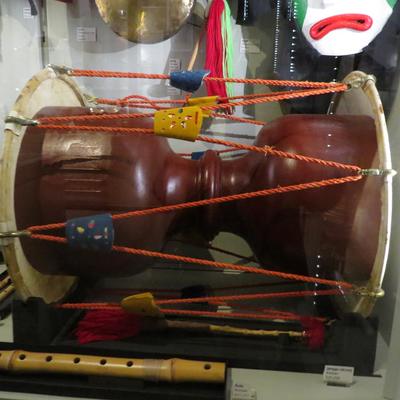

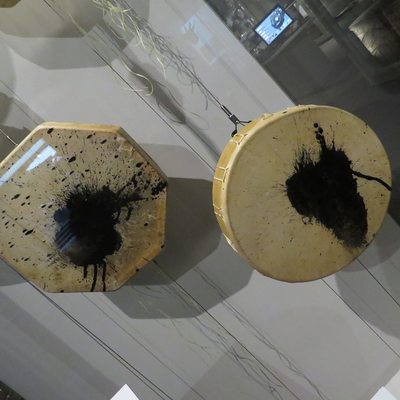

I had the opportunity to visit the University of British Columbia and the Museum of Anthropology in Vancouver. I show these percussion instruments to illustrate, despite differences in construction and visual presentation, the sound that emerges from these instruments serves as a universal language bringing people together.

Crocodile River Music Ensemble

This summer, I had the opportunity to meet the members of this group. They are cultural ambassadors in education from different regions in Africa. They bring art, music and dance to communities in the United States. The construction of these instrument and their names will be discussed later.

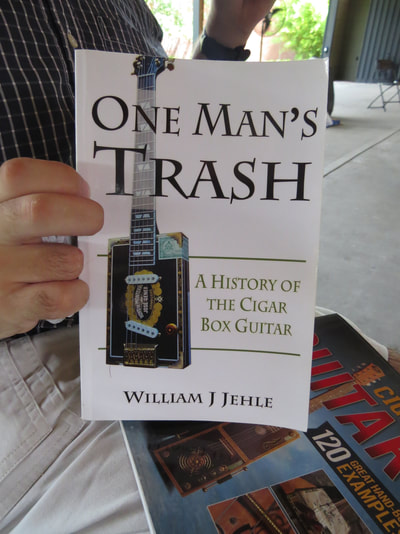

Cigar Box Guitar Workshop

Variation of plucked chordophone instrument, made from household items--popularized during the Great Depression in the United States

The Mayohuacan

A Taino Indian drum used for ceremonial purposes, like the "Areito": a dance honoring the gods

Constructing the mayohuacan

The Making of a Cuatro

cuatro: a ten-string chordophone instrument with with five sets of double-coursed strings, sounding an octave lower than written--refers to the modern version of the instrument used in Puerto Rico and other areas of Latin America and the Caribbean

Luthier Jaime Alicea

Luthier Jose Luis Mercado

With luthier Angel "Wimbo" Rivera

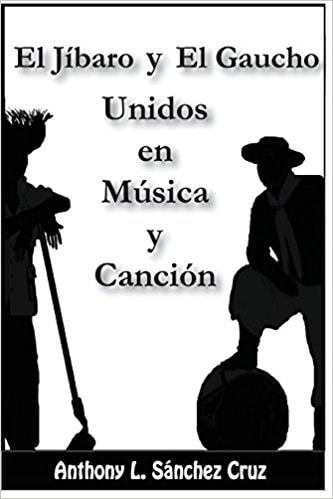

El jíbaro y el gaucho unidos en música y canción (2018) (Spanish Edition)

Paperback

Publisher: Ditrie Marie Bowie

Link (Amazon): amzn.to/2wdiOlq

"English Edition" Now Available on Amazon: amzn.to/2WtgNNL

This book was presented as part of a lecture at the 2018 Isabela Tango Fest on June 23 in Isabela, Puerto Rico.

Paperback

Publisher: Ditrie Marie Bowie

Link (Amazon): amzn.to/2wdiOlq

"English Edition" Now Available on Amazon: amzn.to/2WtgNNL

This book was presented as part of a lecture at the 2018 Isabela Tango Fest on June 23 in Isabela, Puerto Rico.

Musical Innovations from Three Different Eras: A Collection of Essays (2012)

E-Book

Publisher: Spectacle Publishing Media Group

Link (Barnes & Noble): bit.ly/2OGTU5o

E-Book

Publisher: Spectacle Publishing Media Group

Link (Barnes & Noble): bit.ly/2OGTU5o