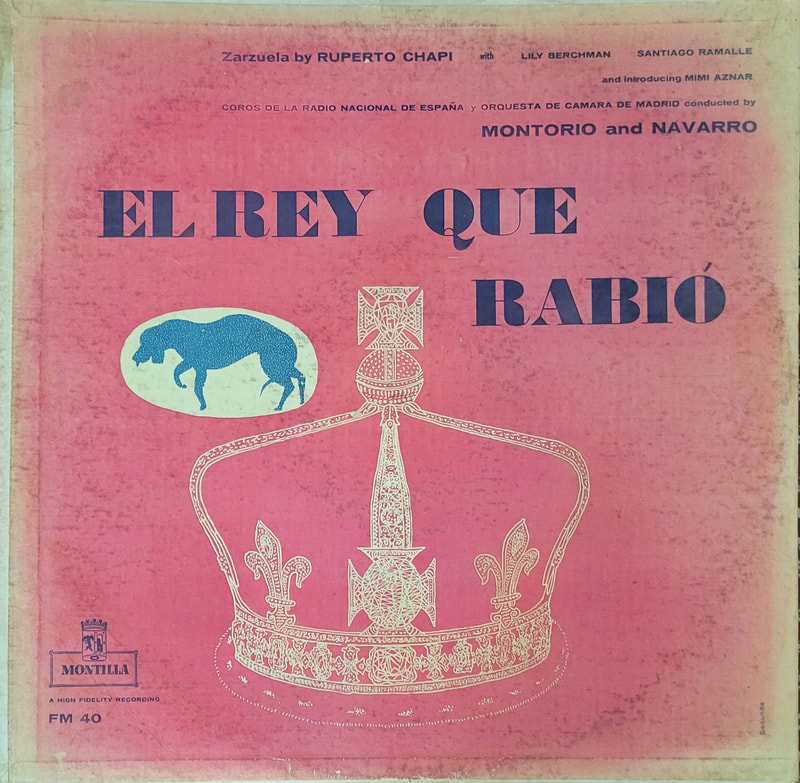

El Rey Que Rabió[1], by contrast, is a comical zarzuela in three acts that presents another side to Spanish classical music from the late-nineteenth century beyond composers like Isaac Albeniz (1860-1909) and Enrique Granados (1867-1916). A zarzuela functions as an operetta in the Spanish language instead of in English. The recording featured in my library consists of selections from El Rey Que Rabió. Composed and premiered in 1891, with the libretto by Miguel Ramos Carrión and Vital Aza, the plot largely centers around a king who grows bored of his duties as a monarch one day that he decides to travel alone in disguise to find out what the citizens really think about him as a leader… much to the alarm of his assistants. Given the era in which it was created, I perceive this work as parodying the Spanish monarchy and its gradually crumbling colonial presence in the Americas and Asia. This becomes especially apparent when watching the full production and seeing the cast dressed in intentionally funny, borderline-ridiculous regal attire. The complete performance of El Rey Que Rabió (with visuals and a duration of over two-and-a-half hours) is currently available online from the Teatro de la Zarzuela from Madrid, Spain and presented with Castilian Spanish subtitles.[2]

[1] The title roughly translates to The King Who Went Mad.

[2] That specific performance occurred in 2021 at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Viewers will notice that, to ensure the safety of the performers, most of the singers wore face masks in addition to the elaborate costumes.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed