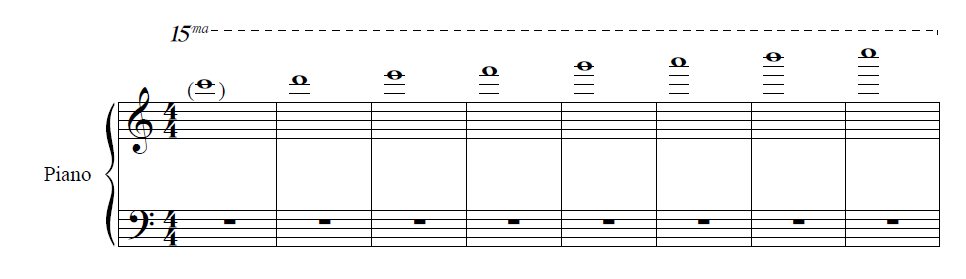

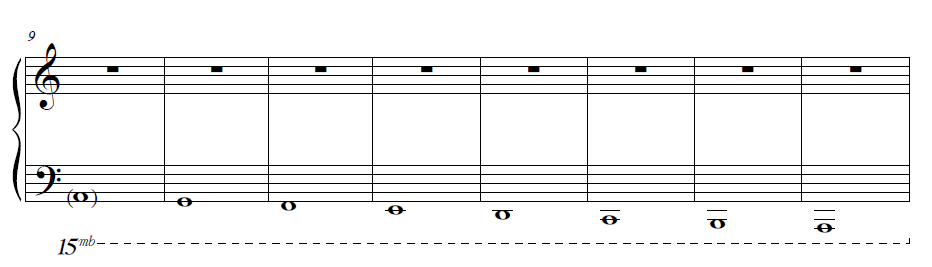

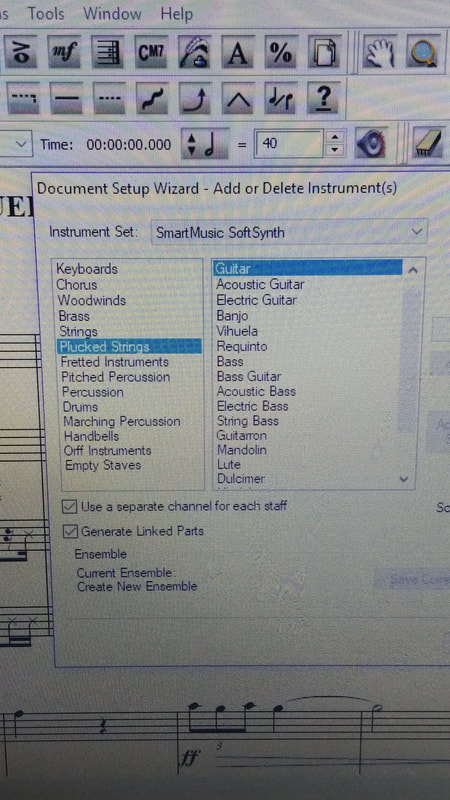

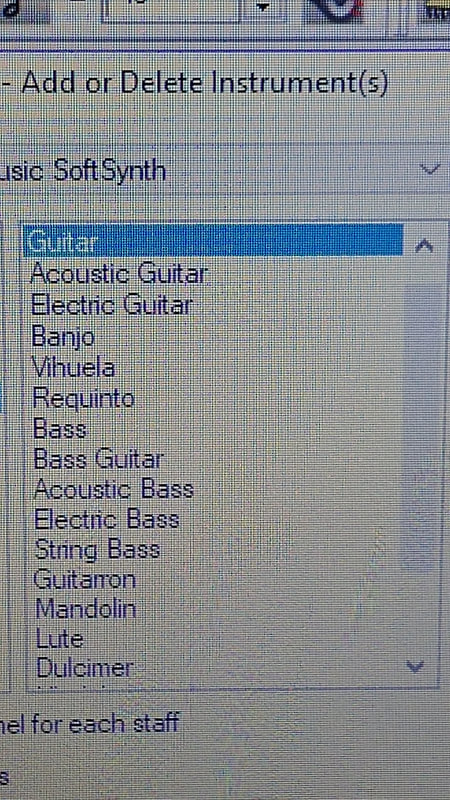

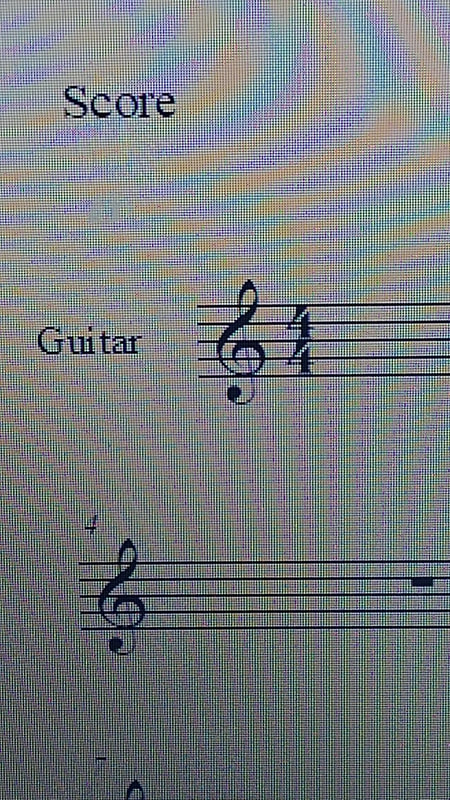

For those who want to see and hear what the Finale music notation software program interprets "unplayable" notes-- meaning, how the program interprets tones outside the normal range of an instrument under "Equal Temperament" tuning-- here is how Finale can interpret such notes on a piano. I present visual examples of the highest and lowest notes on a normal piano keyboard (the standard 88-key format, excluding the Bösendorfer grand pianos, which include extra keys). I, then, follow these with a short video of the Finale MIDI playback (For best audio results, it might help some viewers to increase the volume.).This quick post serves as a reminder to composers who use the Finale music notation software that researching and editing instrumental parts is equally as important as writing a piece of music. Guitar parts usually feature a treble clef with a number 8 below it, meaning that the pitches sound an octave lower than written. For some odd reason, the version of Finale that I use (Finale 2011, which is outdated, but still usable) omits this type of treble clef when choosing a guitar part. Trying to correct this problem by using the correct guitar clef often results in all of the notated pitches shifting down an octave, which is visually unpleasant because it can produce strange ledger line notes.

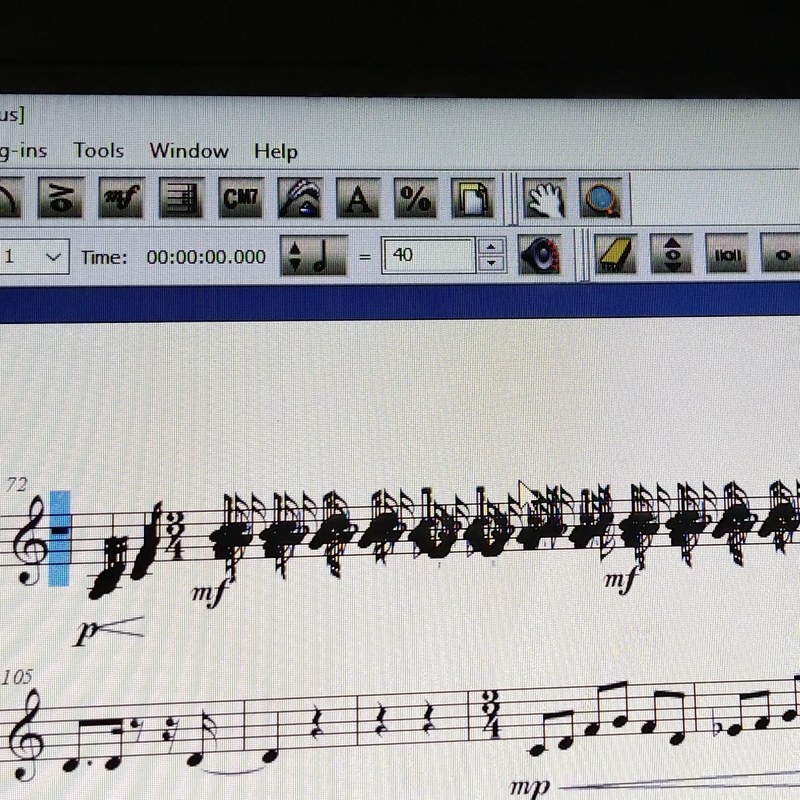

It also deserves mention that a musical score and part must be presented as neatly as possible. Although I present the last photograph at the bottom primarily for laughs, I also do it to demonstrate why composers should write for human musicians and not for the notation software. Music notation software programs like Finale have a tendency to present visual oddities or perform high or low pitches that sound possible in playback. In actually, such notes would be unplayable because they would be out of range. Perhaps, in a future post, I will provide brief aural examples of what I mean concerning this last point. Yesterday, I had planned to create a new YouTube video of myself performing older piano music. In this case, it was the Gnossienne No. 2 from 1890 by French composer Erik Satie (1866-1925). I recorded the performance on my console piano, which (regrettably) has required re-tuning for the past fifteen years or so, using the Lexis Audio Editor smartphone application. The following video illustrates my frustration over what I heard after I transferred the audio file into the Audacity freeware music program for editing: What possessed me to stop the playback of this recording in disgust? The problem, or at least what I heard, stemmed not with the poor sound quality of the flat piano. I took greater issue with how I captured the sound recording with Lexis Audio Editor. I set the recording level at +13 dB in stereophonic mode and placed my smartphone on the fallboard of the piano. This last step proved to be a disaster, because Lexis capture the loud tones of the piano (which also produced "clipping," or an annoying scratching sound) while also silencing the softer tones. Experienced electronic and electroacoustic composers, as well as skilled audio engineers, try their best to avoid clipping and other errors in audio sampling and editing: things like "Quantization Error," which can happen when converting sounds from analog to digital, and "Aliasing," or an aural error that often results in the distorted quality of a given audio file. The cleaner the sound quality of an audio file, the better.

For those who are curious, here is a YouTube link that should clarify what I have said: bit.ly/2UGPcZ5 |

AuthorDMA. Composer of acoustic and electronic music. Pianist. Experimental film. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed