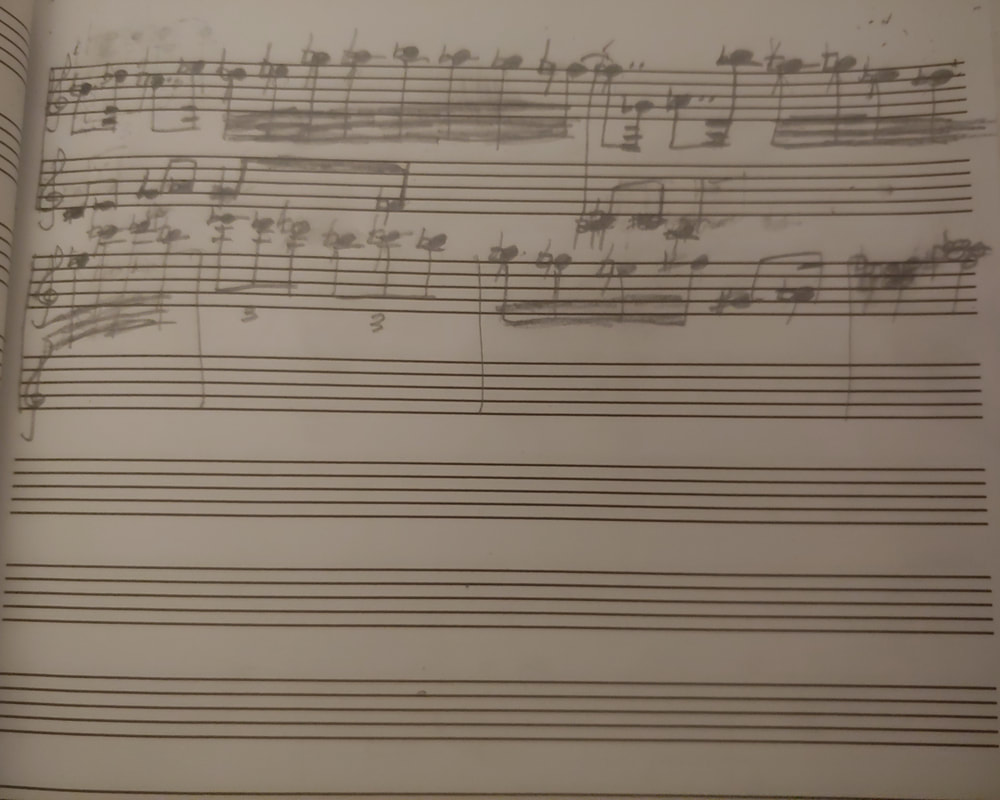

I began working on this programmatic chamber piece in the Fall of 2013. After experimenting with non-traditional and Twelve-Tone compositional techniques, I wanted to create a piece that maintained a tonal structure (albeit, within a Post-Modern musical context). The Legend of Chufle underwent multiple changes in concept and instrumentation (I originally wanted to write a nocturne for clarinet, vibraphone and piano based on owl calls). I chose to score this work for flute and piano because of the simplicity and sonic richness.

Like the subtitle of this piece suggests, I had viewed The Legend of Chufle as a musical poem. I later took this idea a step further by deciding to include text that would accompany this piece. I collaborated with poet Ditrie M. Sanchez-Bowie (b. 1984), who wrote the text based on how she viewed the music. Although I originally drew musical inspiration from works by French composer Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) and American composer Richard Danielpour (b. 1956), she heard my work as idiomatic of Native American music. As a result Sanchez-Bowie created an epic poem about a Native female chieftain named Chufle.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed