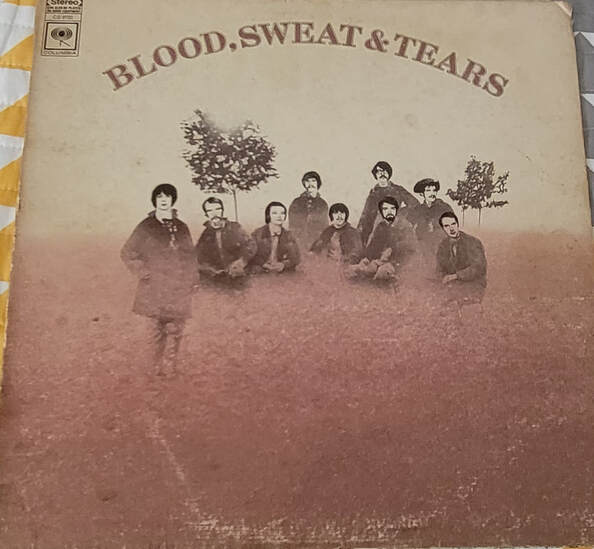

Year Released: 1968

Composer/Artist(s): Blood, Sweat & Tears

Record Label: Columbia

Genre: Jazz-Rock

It has been awhile since I last wrote on here. Rest assured, I did not forget about my record collection. Let us continue this exploration with Blood, Sweat & Tears: a rock group based in New York City that incorporates multiple musical elements-- primarily, jazz and (occasionally) classical music. This band must be understood as a supergroup, active since the late 1960s and continuing into the 2020s, with different members over the decades. The 1968 Grammy-winning self-titled album featured the following nine members in the band at that time, many of whom also helped to arrange the ten tracks on this album:

- James Thomas Fielder: Bass

- Steve Katz: Guitar, Vocals

- Chuck Winfield: Trumpet, Flugelhorn

- Lew Soloff: Trumpet

- Bobby Colomby: Drums

- Dick Halligan: Keyboards, Flute

- Fred Lipsius: Saxophone

- Jerry Hyman: Trombone

- David Clayton-Thomas: Lead Vocals

- Of the tracks that stand out to me, let me begin with “Variations on a Theme by Eric Satie (1st and 2nd Movements)"—This track opens the album with an arrangement of the Gymnopedie No. 1 by French composer Eric Satie (1866-1925)-- who also more commonly went by the name Erik Satie. In this case, Blood, Sweat & Tears focuses on using a fragment of the opening melody and expanding it with flutes brass, drums, and what sounds like a “flange” effect. This piece also serves as a cyclical end to the album, because the first movement reappears as the the final track… with the sound of footsteps (The album credits a Lucy Angle for providing that effect.)

- “And When I Die”—The band experiments on this track with what sounds like a combination between Gospel/Spiritual and Country Western music. The lyrics and thematic material, on the other hand, appear to contradict this musical backdrop and can come off as blasphemous for some listeners: specifically, the overall approach to not fearing death.

- “God Bless the Child”—This is a cover of the Billie Holiday jazz standard—a song which Holiday had recorded several times. The version by Blood, Sweat & Tears is radically different in terms of tempo, vocal delivery, and instrumentation. The pacing is slower in the beginning and the end, with a slight tempo increase at the “bridge” and David Clayton-Thomas sings the lyrics in a soulful manner. The real surprise with this cover comes in the instrumental middle section that unexpectedly incorporates Latin Jazz at a faster tempo. While that inclusion seems rather random and out of place, it somehow works.

- “Spinning Wheel”—I find this track interesting not just because of the incorporation of brass and drums. Like “God Bless the Child,” “Spinning Wheel” also changes the musical mood: specifically, towards the end where the ensemble imitates a carousel, followed by random banter and laughter.

- “Blues—Part II” This track is more like a long series of improvisations with solos for organ, drums, and saxophone. David Clayton-Thomas also sings towards the end, belting out vocalization reminiscent of soul music

RSS Feed

RSS Feed