|

(This video works best when viewed in the mobile version of YouTube. The "Desktop" version produces a white background in "Standard" mode, while the "Full Screen" mode uses a black background.)

0 Comments

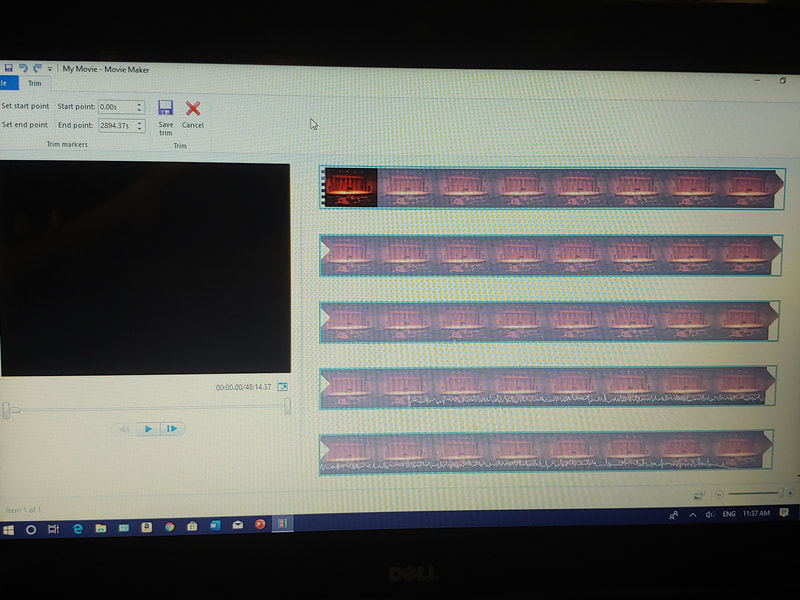

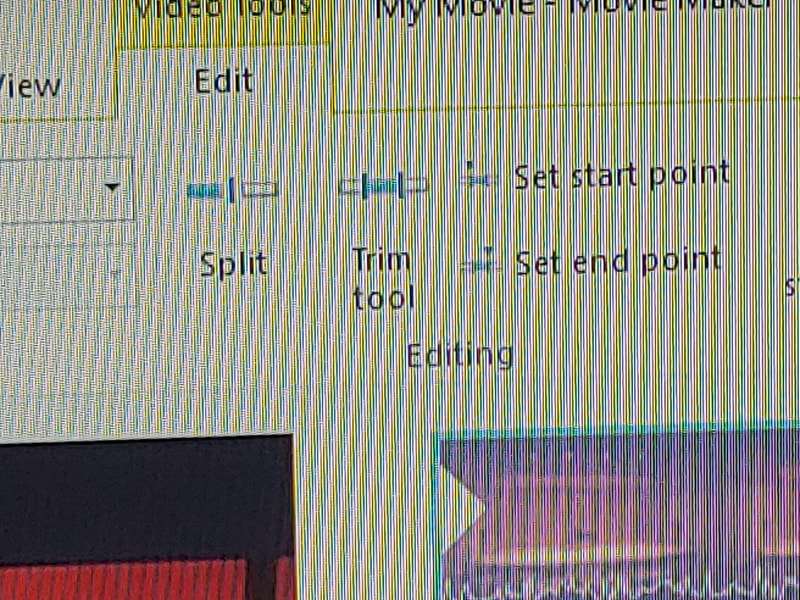

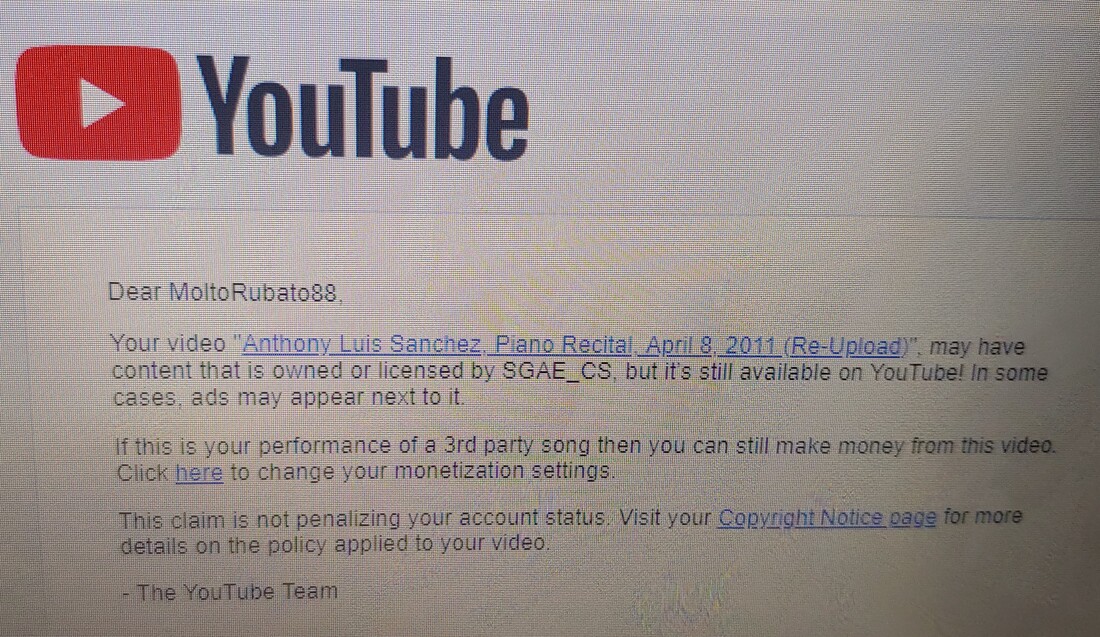

Last week, I devoted a lot of time to discussing the absurdities surrounding copyright claims of classical music performances. Some readers might recall how I mentioned that I would need to go back and edit the piano recital video that featured the Satie Gnossienne No. 5 (which had been claimed by Naxos of America). True to my word, I used the Movie Maker film editing program last Friday to remove the segment of the recital video that initially caused the trouble. This process was necessary because, after I removed that track from YouTube, I still needed to fix the entire video because YouTube muted the majority of the Gnossienne No. 5 in my original video: an omission that became too obvious the more that I saw and heard it. Fixing the video in Movie Maker meant applying the "Split" tool to the original video. Doing this required locating good starting and ending points and deleting that segment from the video. I found this tool more practicable than the "Trim" tool, because "Trim" had the tendency to accomplish the opposite: deleting everything else from the video and leaving the problematic muted section that I needed to erase. I uploaded the fixed version of the video to YouTube, albeit with an additional disclaimer in the video description explaining why I had to delete the Satie Gnossienne No. 5. I also decided to keep the original on my channel because the recital involved years of practice and hard work. I was not planning on taking down that video, anyway. I thought that I had resolved the problem by re-uploading the video without the claimed content. That was, until I received an e-mail message about my re-uploaded video about a half-hour later that same day. At this point, I grew both frustrated and suspicious. I felt frustrated because I just spent time trying to fix the copyright claim problem, but I was also suspicious because I needed to know more about this "SGAE_CS" (I had seen their name before in a similar message that I received back in May after I removed the claimed piece from the original video.). Upon checking the detail, this company had claimed the rights to the Prelude en Tapisserie (another Satie piece that I performed on my recital). Out of curiosity, I Googled "SGAE_CS" and found that the they are a fake company that scams YouTubers by establishing false copyright claims. What is worse is that this scam has been happening for years to many YouTube content creators. I recently tweeted to YouTube about this problem, but they have yet to respond. It may be time for me to dispute a copyright claim against SGAE_CS. Just saying...

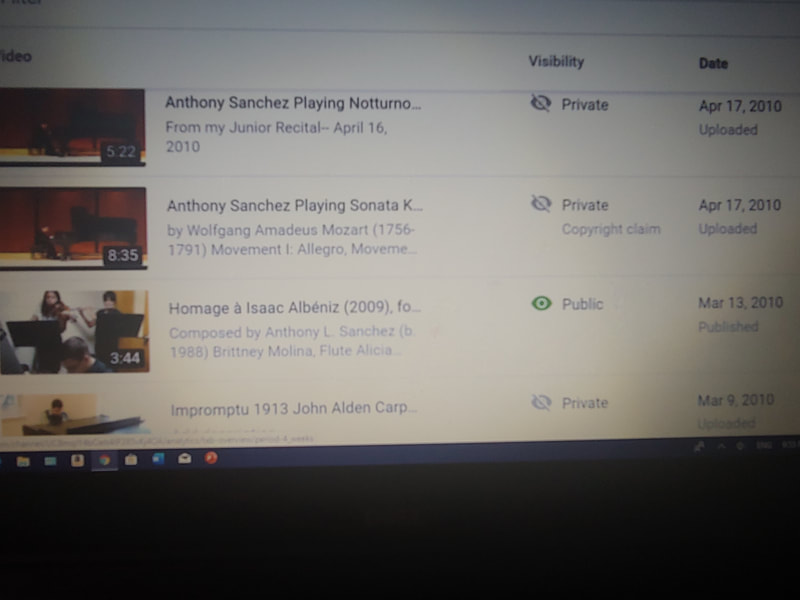

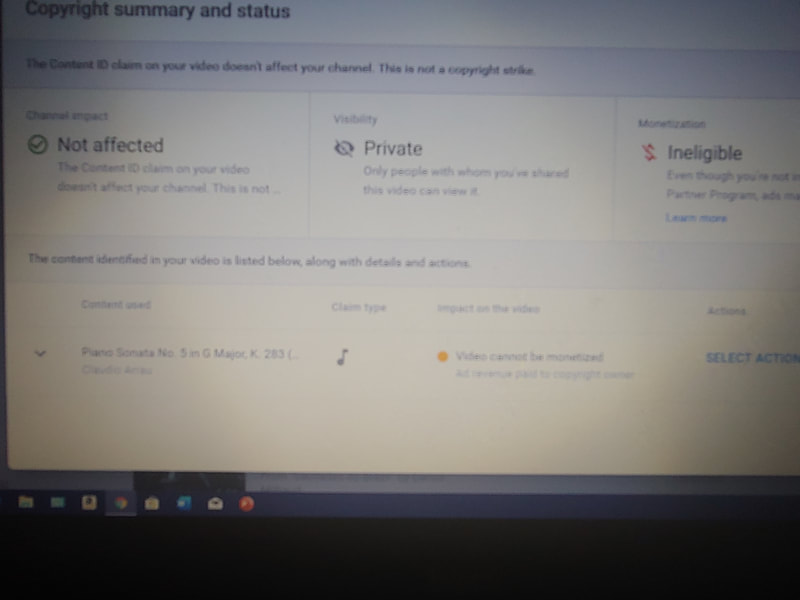

I did not intend to create a follow-up post concerning copyright rules on YouTube and classical music. However, after seeing my previous blog entry has been gaining a lot of attention, I feel that I must create another one. This decision is necessary because I realize that I neglected to mention a few significant points about copyright on YouTube. While I mentioned these points on other social media pages the other day, I wanted to be able to explain them here in a little more detail: specifically, for those who are not familiar with how YouTube and explains copyright problems. Let me begin by saying that the situation involving my student recital was not the first time that I encountered issues with copyright. In fact, I started getting copyright claims for videos of my piano performances that I uploaded to YouTube in 2010: the year that I launched my MoltoRubato88 channel. Other record labels claimed that they owned the copyright to music by Mozart and Grieg. However, I did not need to delete these videos from my channel. I decided to keep them and mark them as "Private." If a YouTuber has a copyright claim on a specific video on their channel, than the notification of that claim will appear in the "Videos" section of the YouTube Studio (YouTube Studio is currently still available as a beta version.). From there, the user can check the details concerning the copyright claim: who claims the music in question and possible options for monetizing the video. These options usually involve sharing the profits (accrued from advertisements on the video) with the copyright holder. Of course, monetizing videos on YouTube only works through establishing an advertising account from Google. With regard to the third screenshot shown above, a copyright claimed video on YouTube can still stay on a channel. What this means is that the video (in certain cases) cannot be monetized by a YouTuber on their channel, because the video was claimed by someone else.

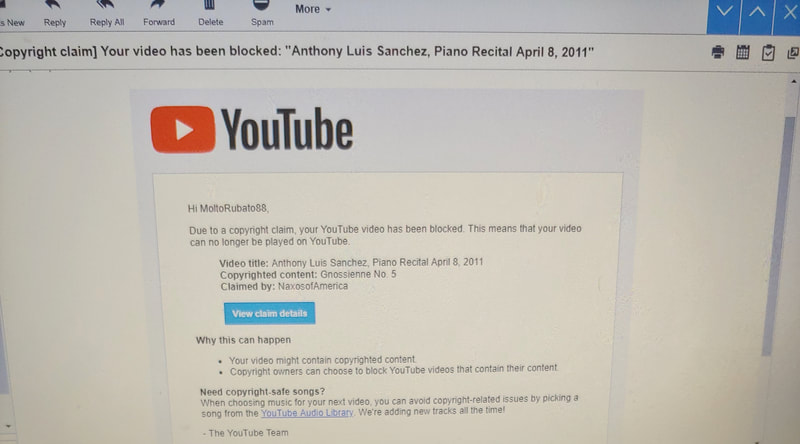

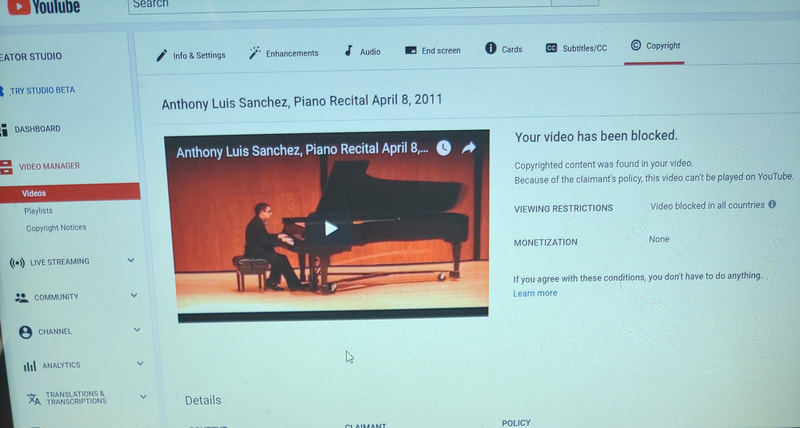

It deserves mention that a copyright claim does not mean the same thing as a copyright strike. A copyright strike often caries more severe penalties for YouTubers, specifically for those who intentionally upload copyrighted materials to their channel without permission from the copyright holder(s). A copyright strike can often prevent a YouTuber from monetizing and live streaming videos on their channel. YouTube implements a "Three-Strike" policy in their "Community Guidelines." Three copyright strikes on a YouTube channel result in permanent negative effects: account termination, the removal of all uploaded videos on the affected channel and banishment from the YouTube community. In other words, while a copyright claim is frustrating and requires certain procedures to fix, it is not as damaging as having a copyright strike. 89Two weeks ago, I came across an unsettling e-mail message. YouTube blocked one of the videos on my channel (MoltoRubato88) in all countries back in late April due to a copyright claim. At first, I thought that they were joking, because I am usually careful with the content that I post to my channel. Upon further inspection of the e-mail message and copyright claim, it turns out that YouTube was serious. They removed a video that I posted years ago of one of my student piano recitals from when I was a university undergraduate. What offending piece in question got the video blocked? It was the Gnossienne No. 5 (1889) by Erik Satie (1866-1925). That's right. A video with a piece written by a composer who has long been dead for over ninety years got blocked.

How was this even possible? Why did it happen? More importantly, how did I solve the problem? Looking closely at the screenshot on the left, you will notice that the record label "NaxosofAmerica" owns the copyright to the audio recording of the piece. Even though music written and published before 1923 belongs within the "Public Domain," this rule only applies to published musical scores and not audio recordings of music published before 1923. That means that, if you are a musician who wants to post video recordings of performances of music by Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, or whichever composer has been dead for centuries, you have to ask for permission from the record label that claims copyright to their music. This sounds ridiculous (because it is), but is also happening elsewhere. Just last year, a pianist from Australia had his video performance of music by J.S. Bach removed by Sony Classical on the grounds of a copyright claim. Of course, this situation also backfired when Sony realized that they did not really own the copyright to Bach. Where does this leave the musicians. though? If recording companies can freely block any performance for nonsensical reasons on YouTube, then there are several steps that musicians should take to protect themselves on that social media platform. They can remove the piece in question that is under copyright from their video, mark their video as "Private," re-upload the video without the offending piece, or (worst-case scenario) file a counter-claim complaint and fight back. This last step can be rather dangerous, because it usually involves legal action and money. In situations like the one that I encountered, sometimes it is best to just comply and re-upload the video without the copyrighted content. I will need to do that with my recital video to avoid future complications. The details discussed here sound very troubling when taking all of these factors into consideration. However, there may be some hope amid this mess, thanks to the passing of the "Music Modernization Act" earlier this year. Some of the rules regarding copyright and audio recordings-- at least, as they apply to United States copyright law-- might change, such as relaxing the Public Domain restrictions on sound recordings released before 1956 (which, as the rules previously stood, would expire in the late 2060s). Before I show the following video, I must inform my readers that I have been sick for the past few days (since last Saturday) and have been recovering from a fever and virus. I managed to create the video a few days ago while recuperating. The visuals actually serve as a re-cut version of an older YouTube video that I created last year where I filmed near Charleston, SC. The superimposed visual effects stem from the Glitcho smartphone app and the Quick Video Editor (a built-in, albeit limited, video editing program for Android smartphones). I originally included a recording of myself playing the Gnossienne No. 3 (1890) by French composer Erik Satie (1866-1925). However, I decided to remove the track due to a recent YouTube copyright claim problem that I recently resolved concerning another one of his Gnossiennes (an anecdote which I will save for another post) . Because my sickness largely prevented me from accessing my laptop to compose, I had to settle for creating a stereophonic electronic work that combined different music composition and sound recording/editing apps from my phone. I used Infinite Pads and Keuwl Music Pad to generate different sounds and drones, while I used Lexis Audio Editor to apply echo and reverb effects, in addition to decreasing the speed of the track. (This video works best when viewed in the mobile version of YouTube. The "Desktop" version produces a white background in "Standard" mode, while the "Full Screen" mode uses a black background.) (This video works best when viewed in the mobile version of YouTube. The "Desktop" version produces a white background in "Standard" mode, while the "Full Screen" mode uses a black background.) |

AuthorDMA. Composer of acoustic and electronic music. Pianist. Experimental film. Archives

July 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed