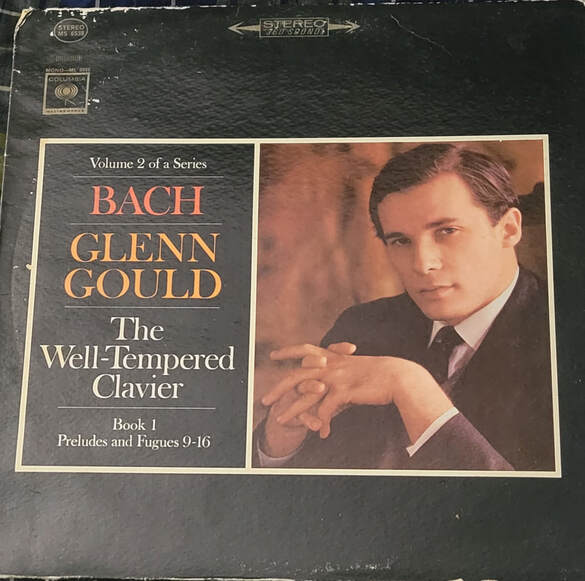

Label: Columbia Records

Year Released: 1964

Composer/Artist: Johann Sebastian Bach (composer), Glenn Gould (pianist)

Genre: Classical (Baroque), Piano

When I began this blog series about audio recordings in my collection, I initially planned to avoid featuring classical music albums. My reasoning for that stemmed from what I had discussed in previous blog posts: mainly, the glaring problems with classical music and cultural (mis)representation. I also had to consider that I would be severely limiting my audience if I only focused on that genre. Also, from my perspective as a composer, it helps to gain exposure to multiple popular music genres: many of which adhere to formal structures and break social stereotypes. It is with those contexts that I approach this current discussion. The music may derive from an older time period associated with "classical" music, but the unconventional way that it is performed links it to the twentieth century.

The Well-Tempered Clavier: Preludes and Fugues, Book 1 (Preludes and Fugues 9-16) serves as part of a multi-volume series of keyboard music by Baroque composer Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750), as played by Canadian pianist Glenn Gould (1932-1982). This is not the first time that I have heard these pieces on audio recordings. I have heard these pieces on the 1984 Andras Schiff double CD compilation (and and his interpretation of the second book of The Well-Tempered Clavier). Things take a markedly different turn with how Glenn Gould performs Bach when compared to other interpretations. Listening to "Prelude and Fugue 9-16" on the vinyl record, I noticed the following:

1) Choice of tempi—Gould takes certain preludes and fugues at either faster, or slower tempo markings than initially prescribed in the scores.

2) Pianism—Gould takes some liberties with these pieces by preferring to use a detached style of playing: incorporating legato and staccato in unexpected areas.

3) Humming— Yes, humming. That characteristic can be found in many Glenn Gould piano recordings. This Bach album is no exception. Upon first listen, the humming sounds like mistakes on the album that the recording engineer forgot to remove. That aspect of the album is intentional, though. Glenn Gould would frequently hum along with the music throughout his recorded performances. (I recommend using headphones when listening to his recordings, because people can get a better grasp of what I mean.). While traditionalists might scoff at that technique and allude to its distracting nature, it also demonstrates that Gould was able to break the strict rules of piano performance etiquette. By humming while playing, he was able to feel the music. In this respect, audiences do not just hear an interpretation of Bach. They get to experience it through the musical process by the performer. It should also be noted that the legacy of Glenn Gould and his recordings (which range from his interpretations of music by Bach, to the twentieth century with composers like Alban Berg and Paul Hindemith) are currently preserved online through a commemorative website and social media platforms.

I should also add one important detail concerning this specific Bach album and acoustics. The Glenn Gould recording of “Prelude and Fugue 9-16” from Book 1 of The Well-Tempered Clavier functions as a performance of music by Bach for more contemporary audiences. Gould plays the music on a modern piano that uses “equal temperament” tuning, where the octave is (theoretically) subdivided into twelve semitones. That approach might work well for piano music from the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, but it does not work for keyboard music written before the twentieth century. The fault does not lie with Gould, but in the incorrect tuning system. Michael Rubenstein has illustrated through mathematics that “well temperament” signifies a completely different tuning system than “equal temperament.” Well temperament (sometimes called "unequal temperament") tries to solve the glaring problems with certain intervallic divisions (thirds and fifths) and key limitations of “meantone temperament” by offering more sonic possibilities and musical key options based on the “Circle of Fifths”). Equal temperament subdues those sonic possibilities by (unsuccessfully) trying to evenly divide the octave. When it comes to interpreting older keyboard pieces (including repertoire from the Classical and Romantic eras), some musicians prefer more historical accuracy by applying the “Thomas Young” well temperament from 1799. While Michael Rubenstein does discuss this type of keyboard tuning, I find it more beneficial to hear the differences between this and equal temperament. Those looking for more information about different acoustical systems should consult How Equal Temperament Ruined Harmony (And Why You Should Care) by Ross W. Duffin.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed